9 Small N

By Justin Zimmerman

9.1 Introduction

The field of political science has traditionally focused on the importance of hypothesis testing, causal inference, experiments and the use of large n data. Quantitative methods in all its capacities is without a doubt important, but what can be lost at times is the value of small n methods of inquiry within the field of political science. Researchers such as Kathy Kramer, Cathy Cohen, Reuel Rogers, and Jennifer Hochschild et. al. have all used small n methods to tell stories about particular groups that have rarely been highlighted in political science. Whether its identifying rural consciousness in Wisconsin (Kramer 2016), researching the secondary marginalization of the most disfranchised in the black community (Cohen 1999), explaining the unique political stances of Afro-Caribbean immigrants (Rogers 2006), or highlighting the politics of a new racial order (Hochschild, Weaver, and Burch 2012), small n data can allow for a researcher to discover new information not easily attainable through quantitative methods alone. Small n methods allow for a more in depth assessment of a particular area and people.

This chapter will focus on the importance small n research. The chapter will highlight the various methods for conducting small n research including: interviews, participant observation, focus groups, and process tracing, as well as the various procedures for determining case selection. First, the chapter will elaborate the differences and goals of small n research as compare to quantitative research.

9.2 Background

To be a well-rounded political scientist it is important to understand that not every question can be answered through quantitative methods alone. There are times when small n methods are the more appropriate option. Yet, how does a researcher decide when small n methods are appropriate for their research? The researcher must be able to identify the differences and purposes of small n qualitative research and quantitative research. First, quantitative research focuses on the effects of causes, while qualitative methods is focused on the causes of effects. In other words, quantitative research, especially with regards to causal inference, aims to figure out if a particular treatment causes a particular outcome, such as an increase in an individual’s education causes them to be more political mobilized.

Small n qualitative research on the other hand focuses on understanding how the outcome came to be. American Political Development (APD) scholars are a great reference to this line of thinking. APD scholars look to track why certain outcomes came to be, such as Paul Frymer’s work on Western expansion in the United States of America (Frymer 2017) or Chloe Thurston’s research on housing policy and how it has historically discriminated against women, African Americans, and the poor through the use of public-private partnerships (Thurston 2018). Small n qualitative research also includes oral histories such as those provided by Yolande Bouka concerning the Rwandan genocide (Bouka 2013) and the interviews and historical context to explain the coercive power of policing in Latin America as researched by Yanilda María González (González 2017). In short, small n qualitative research aims to tell a story of how an event or policy came to be, and what are the experiences of particular groups because of a particular event or policy.

Thus, a small n qualitative researcher must take care to ensure their work is able to satisfy three characteristics of good qualitative research. First, their research must emphasize the cause and the implications it has. Second, good small n qualitative theories must explain the outcome in all the cases within the population. Lastly, qualitative questions must answer whether events were necessary or sufficient for an outcome to occur, with the cause providing the explanation. To setup qualitative research it is important to that understand that qualitative methods are interested more in the mechanisms behind things. Small n approaches can help us explore the underlying process such as how institutions evolve and change by gathering data about institutions, but it can also be answered through looking at institutional change in one or two contexts. Small n qualitative research can be inductive as a researcher builds the theory and hypotheses from the data, or deductive by testing theories and hypotheses with the data. What is critical in building qualitative research whether inductively or deductively is case selection.

9.3 Case Selection

Case selection for small n qualitative research setup to use a small number of cases in order to go into a deep dive into a specific subject. For instance, a researcher may use a specific neighborhood to explain a specific political characteristic of the community. Reuel Rogers conducts this exact research when he interviewed Afro-Caribbean residents in New York City about their political preferences as new immigrants of the United States of America (2006). This case selection allowed for Rogers to assess the veracity of an age old claim that pluralism allows for immigrants to eventually assimilate into American culture and government participation by highlighting the complexity that comes from immigrants that are identified as black. Rogers finds that Afro-Caribbean immigrants suffer from discrimination that may hinder their ability to assimilate into American society. Yet, how does a researcher decide what cases to use? Seawright and Gerring provide some insight by identifying seven case selection procedures (Seawright and Gerring 2008). For the purposes of this text, this chapter will focus on four of these case selection procedures. The cases focused on will be most similar, most different, typical, and deviant. The chapter will also briefly describe extreme, diverse, and influential cases.

9.3.1 Most Similar

Seawright and Gerring instruct the use of the most similar case selection must have at least two cases to compare. Ideally, when using most similar cases all independent variables other than the key independent variable or dependent variable would be similar. For example, we may compare neighborhood with similar variables for income, religion, and education with the key independent variable such as race being the only difference. Thus, a researcher could use small n case selection to research differences or similarities that black middle class residents of particular neighborhood have with a white middle class neighborhood. It should be noted that matching any particular cases by exact characteristics is essentially impossible in the social science. Thus, this technique is daunting to say the least. Yet, part of the compromise of political science and social science in general is doing the best with the information you have and being honest about the limitations. This is especially important in the use of the most similar case selection procedure.

9.3.2 Most Different

Gerring and Seawright also identify the use of the most different case selection procedure. The most different case refers to cases that are different on specified variables other than the key independent variable and dependent variable. For instance, maybe there are class, education, and religion differences between two neighborhoods, but the key independent variable of race remains the same for both. Gerring and Seawright argue that this tends to be the weaker route to take in comparing two case but nonetheless it is an option to use for a small n researcher under the right circumstances.

9.3.3 Typical Case

The typical case refers to common or representative case that a theory explains. According to Gerring and Seawright, the typical case should be well defined by an existing model which allows for the researcher to observe problems within the case rather than relying on any particular comparison. A typical case is great for confirming or disconfirming particular theories. Referring back to the work of Reuel Rogers and his work on black Caribbean immigrants in New York City, Rogers was able to disconfirm Dahl’s argument on plurality allowing for the eventual full inclusion of immigrants by pointing to the racism and discrimination black Caribbean immigrants face that hinders their ability to be fully incorporated into the American polity. What is most important for understanding the typical case is that it is representative and that this representation must be placed somewhere within existing models and theories to be useful.

9.3.4 Deviant Case

Conversely to the typical procedure, the deviant case cannot be explained by theory. A researcher can have one or more deviant cases and these cases serve more as a function of exploration and confirming variation within cases. The deviant case is essentially checking for anomalies within an established theory and allows for the finding of previously unidentified explanations in particular cases. An example may be finding that liberalism is defined differently depending on certain populations which runs counter to Haartz’ assertion that liberalism assumes a certain amount of unity throughout the country. What is most important for understanding the deviant case is for a researcher to check for representativeness of a theory, which allows for much of the value of small n methods. A researcher can tell a story of a particular group that is often assumed to fit the general understandings of political science but through the use of qualitative methods is shown to be more complex than previously understood.

9.3.5 Other Selection Approaches

Along with the four main case selection procedures are other are three other approaches worth noting. The first being the extreme case. The extreme case is characterized by cases that are very high or very low on a researchers’ key independent or dependent variables. It can provide the means to better understand and explore phenomena through the means of maximizing variation on the dimensions of interest in the selection of very low and high cases (Seawright and Gerring, 2008). Unlike in linear regression, where extreme values can provide an incomplete or inaccurate picture, in small n approaches, extreme cases can offer the opportunity for deepening the understanding of a phenomenon by focusing on its most extreme instances. (Collier, Mahoney and Seawright 2004; 4-5)

Second, diverse cases highlight range of possible values. A researcher can choose low/medium/high for their independent variable to illustrate the range of possibility. Two or more cases are needed and this procedure mainly serves as a method for developing new hypotheses. These cases are minimally representative of the entire population

Lastly, influential cases are outliers in a sense that they are not typical and may be playing an outsize role in a researcher’s results. It is unlikely that small n methods will play a significant role as influential cases rely on large n methods.

Check-in Question 1: How should a researcher go about choosing a case selection procedure?

9.4 Method: setup/overview

Small n methods are characterized by an emphasis on detail. A researcher has to be able to see the environment that they are studying. The purpose of small n methods is to gain an in depth knowledge of particular cases. Field notes will be a researcher’s best friend. A researcher should take notes on the demographics, noises, emotions, mores, and much more to gain an accurate understanding of the population they are studying. Additionally, small n methods are about building rapport with the population being studied and constantly taking into account one’s own biases and thoughts as they conduct fieldwork. It is not uncommon for researchers to eventually live in the places they are studying. During her work on the black middle class, Mary Pattillo would eventually move into the South Side Chicago neighborhood of Groveland. The neighborhood was the subject of her book Black Picket Fences (Pattillo 2013). Pattillo would attend community meetings, shop, and cultivate lasting relationships with the community, which would guide her research. There is a level of intimacy needed to do good small n research. Not always to the extent of needing to live with one’s participants, but still a need for insight that goes beyond a shallow understanding of a particular community. Small n qualitative researcher gets at these insights through several methods.

Note: Take sometime to think about for your own research what you are noticing during your fieldwork? How is this informing your study?

9.5 Method: types

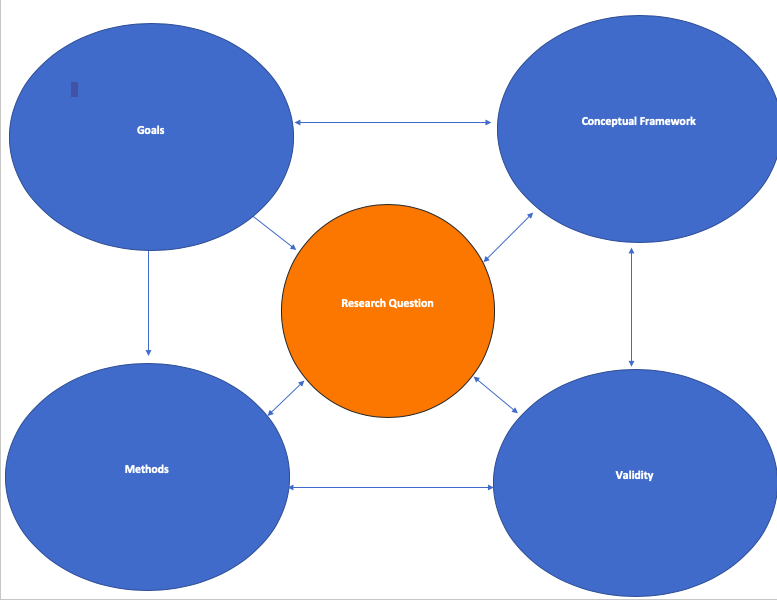

The typical methods used in small n research are interviews, participant observation, focus groups, process tracing, and ethnography. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages and a researcher can utilize more than one these methods depending on the aims of their research. In deciding on a small n method a researcher must consider the goals of the research, validity, and conceptual framework that will feed the researcher’s broader question. The diagram below illustrates that a small n qualitative researcher should be purposeful in their research design. They must consider their overall question. Specify the goals of their research, consider the theories that are driving the conceptual framework of their research, and consider the validity (does it make sense) of their research design.

Figure 9.1: Research Methods Diagram

Focusing on the methods portion of the diagram, this chapter will discuss in further detail each small n qualitative method.

9.5.1 Interviews

Conducting interviews can seem like a daunting experience. A researcher has to develop a comfort in approaching diverse sets of people, many times in unfamiliar environments. A researcher has to be able to build rapport, get their questions answered within a limited amount of time and encourage the participant to elaborate and clarify answers. Interviews are challenging but the good news is there are ways to make the process smoother through organization, commitment, and earnestness.

Before contacting anyone for an interview, a researcher should take sometime to organize their interview guide and decide whether they want to conduct structured or semi-structured interviews. The interview guide highlights the questions and themes the researcher plans to cover during the interview. The format of the interview guide is determined by whether the researcher has a rigid structure of questions they plan to ask each participant (Structured Interview) or a more flexible interview strategy that allows for the researcher to deviate from questions and allow for a more exploratory conversation within the confines of the research question (Semi-Structured Interview).

Once a researcher has decided on an interview structure and completed their interview guide, they can decide who they want to recruit to participate in the interview. The researcher will need to consider the key informants and representative sample they want to recruit. Key informants are experts that can discuss the population of interest including but not limited to academics, community leaders, and politicians. The representative sample is the population that your research is based on. For example, Wendy Pearlman’s text We Crossed a Bridge and it Trembled: Voices from Syria has a representative sample of Syrians displaced during the civil war (Pearlman 2017). What is important to understand about the difference between the representative sample and key informants is that the sample is giving a firsthand account of their experiences, while a key informant is mainly given their observation and experiences of the representative sample from an outside perspective.

Moving on to recruitment, Robert Weiss’ Learning From Strangers lists several reasons that affect whether an individual is willing to participate in an interview including: occupation, region, retirement status, vulnerability, and sponsorship from others within their network (Weiss 1994). Unfortunately, there is no easy way to recruit but from experience face to face discussions with potential participants and immediate follow up are quite effective. Also use snowball sampling to use previous participants acquaintances and networks to participate in interviews. These strategies are not full proof but a layer of personal interaction through face to face contact or networks does have advantages in making many people more receptive to participating in interviews.

Lastly, when the day to interview finally arrives a researcher should have two recorders, tissue, interview guide, consent form, and a gift card for the participant if possible. The interview should not take any longer than an hour as a sign of respect for the time of your participant. A researcher should take meticulous notes during the interview. Also, the researcher must gain the permission of the participant to conduct a follow up interview if necessary.

Check-in Question 2: What is this difference between a representative sample and a key informant?

9.5.2 Participant Observation

Participant observation is a variation of ethnographic research where the researcher participates in an organization, community, or other group-oriented activities as a member of the community. Typically used in anthropology, it involves a researcher immersing themselves within a community. Participant observation requires that the research build a strong bond of trust with the observed community. A researcher (with the help of IRB) will need to decide if participation will be active or passive and whether it should be overt or covert. This can be a particularly sticky situation, as a passive and covert observation may mean community members have no idea they are being studied, while active and overt participation can lead to the environment changing as the community is aware of the presence and role of the researcher. Referring back to the work of Mary Pattillo, recall that she eventually became a citizen of Groveland and participated as any other citizen in community activities (Pattillo 2013). This included leading the local church choir, joining the community’s local action group, and coaching cheerleading at the local park. Pattillo saw her participant observations as essential to describing the black middle class in Groveland and even speaks of the parallels between the Groveland neighborhood and her upbringing in Milwaukee.

The key purpose of participant observations is to provide deeper insight into process and how things function. This exercise is good for ‘theory building,’ but it may be best to include another method, such as interviewing, to allow for the community to tell their story as well, a supplemental method Pattillo uses as well. What is most important when using participant observation (in qualitative methods in general) is to take meticulous field notes with attention to accuracy. A researcher should be cognizant of their own biases and constantly thinking through their analysis to make sure they a capturing an accurate story. In order to tell an accurate story a researcher should keep both mental notes and a notepad. After the end of an event it is important to write everything down while the researcher’s memory is fresh.

Check-in Question 3: What are the advantages and disadvantage of covert and over participant observation?

9.5.3 Focus Groups

Focus Groups, similar to individual interviews requires a researchers to set questions, recruit participants and follow up with participants as necessary. As with an individual interview, the researcher should have an interview guide to help structure the questions and themes of the focus group. The advantage of a focus group is that a researcher is able to facilitate multiple respondents at once, which can lead to additional details and information you might not get in series of single interviews. As seen in Melissa Harris Perry’s Sister Citizen, focus groups are great for spurring discussion about topics such as stereotypes (Harris-Perry 2011). A researcher should note impressions, points of contention, and general interactions within the group. Group dynamics and discussions can be used for theory building as well as getting a deeper understanding of a particular group of people.

9.5.4 Process Tracing

Process tracing is a method of causal inference using descriptive inference over time. Notably used by APD scholars, the goal of process tracing are to collect evidence to evaluate a set of hypotheses through the framing of historical events. There are four tests when discussing process tracing.

The first is the straw in the wind test. The straw in the wind test can increase plausibility but cannot determine that any event necessary nor sufficient criterion for rejecting. It can only weaken hypotheses. The hoop test establishes necessary criterion. Though the hoop test does not confirm any particular hypotheses, the test can eliminate hypotheses. The smoking gun test provides a sufficient but not necessary criterion for hypotheses. The test can give strong support for a given hypothesis and can substantially weaken competing hypotheses. Lastly, the doubly decisive test illustrates evidence that is necessary sufficient. Necessary being when the necessary causes occur when the effect occur and sufficient being when causes always occur after effects.

What is important to understand about process tracing beyond the numerous tests is that process tracing is a good way in political science to draw evidence for certain events and phenomena. Chloe Thurston uses process tracing to track the development of the public-private partnership with regards to housing policy (Thurston 2018). Through numerous historical text including archives, testimonial, and presidential records, Thurston is able to develop a story of how public-private partnerships led to home owning policies that discriminated according to gender, race, and socioeconomic status and how advocacy groups were able to combat these policies.

Thus, process tracing looks for historical evidence to explain certain events or policies.

9.5.5 Ethnography

Ethnography involves studying groups of people and their experiences (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw 2011). As mentioned earlier with participant observations, the purpose of ethnography is for a researcher to immerse themselves in the environment they are studying. The researcher will need to develop relationships with the community and detail the environment through constant note taking and reflection. This is reflected in the work of many of the researchers already detailed in the chapter. Done correctly a researcher can document the emotions, attitudes, and relationships in a community that are sometimes impossible to capture in quantitative work.

In his text Wounded City: Violent Turf Wars in a Chicago Barrio, Robert Vargas is able to capture the fear, frustration, and empowerment felt by the residents of Chicago’s Little Village as they negotiate turf wars between gangs, police, and alderman [vargas2016a]. The insight he is able to gather cannot simply be surveyed, but must be observed in the environment in order to develop trust within the community.

Ethnography is about relationship building and allows for latent findings that may give proper context for understanding particular groups. This is especially important for underrepresented communities, where in depth research is often lacking and responsiveness to a survey may not be likely under less personal circumstances. Ethnography allows a researcher to take a more holistic approach in understanding a community.

Check-in Question 4: What should a researcher be looking for when taking ethnographic field notes?

9.6 Applications

The application of small n qualitative methods is based on a researcher’s question. Sociologist, Celeste Watkins-Hayes, explains that qualitative research is meant to tell specific stories about a community. Going back to the diagram displayed in the beginning of the chapter, a researcher should think of the story they are trying to tell and goals, whether the small n qualitative methods they want to use are valid, and how does all of this relate to the research question. Most importantly when applying small n qualitative methods, record keeping is of the utmost importance. A researcher should make sure that their field notes are detailed and capture an accurate depiction of the environment of study. This means not only self-reflecting on one’s own biases, but also using multiple small n and quantitative methods when appropriate to tell the most complete story possible. Lastly, a researcher needs a method of coding the themes and messages found through their study. Recording encounters and taking good field notes will go far in creating an organized system, which will allow for a researcher to tell an accurate story that captures the nuances and characteristics of a particular community.

9.7 Advantages of Method

Small n qualitative research thrives with gaining in depth information about a limited number of cases. This will allow a researcher to provide insight of a small number of communities that may be missing from large n studies. In this same breath, small n methods allow for theory building that many times is unique to many of the lessons taken for granted in the discipline of political science. It is one thing to ask an individual participant to check an answer on a question about immigration, race, or president. Yet, there is value is going deeper and wrestling with the values, contradictions, as well as the historic and present-day context that make up the politics of a particular people. It is through small n methods that researchers are able to get a better understanding of topics such as rural consciousness, neighborhood violence, and linked-fate. Small n methods allow a researcher to tell the stories that are often ignored, unheard, or misinterpreted through other methods.

9.8 Disadvantages of Method

The major disadvantage of small n methods is that a researcher is working from a small pool. This should not be confused with having less data. Interviews, field notes, and archives bring an abundance of data but the sources are limited. A responsible researcher will have to consider whether their case selection is representative of the broader community and how best to ensure that they are getting a diverse set of voices to hear from to avoid inaccurate assessments of a community. Thus, it is difficult (but not impossible) to generalize from the use of small n research. A researcher including quantitative methods or multiple small n methods in their study will go a long way in strengthening their arguments.

9.9 Broader significance/use in political science

As has been noted numerous times in the chapter, small n qualitative methods allow a researcher to explore groups that cannot necessarily be understood merely with a survey, experiment, or causal inference. Small n allows for a researcher to go into more detail about groups that cannot be fully understood through quantitative research either because they are too small or too unresponsive to quantitative methods. Additionally, small n qualitative research also allows for political scientist to consider context and history when developing claims regarding the political behaviors and institutions that shape society. This context can help a political scientist go beyond superficial understandings of particular groups. For instance, Michael Dawson’s text Black Visions uses quantitative methods to show that African Americans have a high support for Black Nationalism (Dawson 2001). This finding alone could be taken as example of mass black prejudice, as Black Nationalism has been associated most notably with the bigoted views of Louis Farrakhan. Yet, Dawson takes care to include the historical context, including testimonials by leading black thinkers, detailing the long history of debate concerning Black Nationalism, as well as the economic violence and discrimination committed against the black community, which leads to support of some forms of Black Nationalism. Small n qualitative research through the use of history, interviews, and ethnography allows for the telling of these stories, adding complexity and nuance to many of political science’s well established theories and perceptions.

9.10 Conclusion

Not all questions can be answered with a survey and experiment alone. Sometimes a deeper study into a community and event can lead to new and exciting insights in the discipline of political science. Admittedly, small n qualitative research can be met with some cynicism in certain parts of the political science community, but when done correctly through meticulous note taking, coding, and preparation small n qualitative methods can provide insights that have yet to be fully articulated in the discipline and assist in answering some of the most important questions of the day including policing, immigration, and race relations.

9.11 Application Questions

Application Question 1

What are some materials needed to conduct small n research?

Application Question 2

When in the field, how does a researcher build rapport with the community?

9.12 Key Terms

NOTE: this is an incomplete list and it needs expanded!!!!!

covert observation

deviant case

diverse cases

ethnography

extreme case

focus groups

influential cases

interview

key informant

most different

most similar

hoop test

overt observation

participant observation

process tracing

overt observation

representative Sample

snowball sampling

smoking gun test

straw wind test

typical case

9.13 Answers to Application Questions

Answer 1

A researcher should have their interview guide prepared, tissues, and two recorders if conducting interviews or focus groups. Additionally, a researcher should have a notepad for field notes and consent forms if necessary. Business cards are also useful when trying to recruit participants from the field.

Answer 2

Rapport can be built through appearance including dress, race, gender, regional, and class markers. Most importantly, a researcher should present themselves as engaged and attentive to the participants. A researcher should remain professional and read the room, rapport building for a group of blue collar workers may be different than with college students. A researcher should remain cognizant of this distinction and look for openings to build connections when possible.